Bloodstock And Blue Bloods

Horseracing is a British pastime that dates back to the 16th century, and nowhere is this passion more apparent than in the epicentre of the sport – Newmarket and the venerable Tattersalls, where billionaires buy their horseflesh.

By Terrie V Gutierrez

Horse racing is known as the sport of kings and it has been intrinsically tied with the English monarchy since the reign of Charles II in the 17th century.

One story goes that Charles II pursued his mistress, the actress Nell Gwynn, to Newmarket, in Suffolk. There, the lovebirds would stay for long periods of time, away from the court. With nothing to do except wait for their king, the bored noblemen of Charles’ retinue would go to the South Downs and race their horses, and thus, modern British horse racing was born.

The story might be apocryphal at best, but what is known is that Charles II loved horse racing so much that he did build a palace in Newmarket, where he moved his entire court every year. It’s also fact that he put regulations on horse racing in place and followed that up with a formal horse race that adhered to his regulations in 1665. This historic race was called the Newmarket Town Plate and to this day, that race is still run, making it the oldest annually held race in the world. In fact, Charles II himself won that race in 1671, making him possibly the only monarch to also be a horse jockey and win a race.

As the sport grew in popularity, helped along by the monarchy’s interest in it – the interest continues to this day, with Queen Elizabeth II an avid horse racing fan herself – so too did Newmarket. Many racing institutions and related professions and businesses set up shop there, many of which exist to this day. Horses and horse racing are an indelible part of the town. The town sign, for instance has an illustration of King Charles and racehorses while statues of famous racehorses can be seen around town, much as you’d see statues of famous people in other places.

On High Street, you’ll pass by many historic establishments having to do with horses and horse racing like The Jockey Club with the statue of the stallion Hyperion in front. Founded in the 18th century, the Jockey Club Rooms is home to one of the finest collections of equine art and historical artefacts given by members over the years. Beside the Jockey Club Rooms is a horse racing museum. A block away is the famous Tattersalls, the oldest bloodstock auctioneers in the world.

And of course, the horses are a common sight. Cars are very much secondary here. It is estimated that there are about 3,000 horses across 70 training yards at Newcastle. Most of the successful trainers are based here as well. The best time to see these magnificent creatures is in the morning, when jockeys and trainers walk them through town to train at the grass slopes of Warren Hill. With their different uniforms, it is easy to identify which horses are under which trainer.

The trainer

One of the most well known trainers in Newmarket these days is Hugo Palmer, himself a member of the nobility; his father is the fourth Baron Palmer. Palmer, who got his licence to train in 2011, makes his base at Kremlin Cottage Stables, one of the more established stables in the county. Since his start eight years ago, he’s had an admirable strike rate and 35 Stakes winners under his belt, making him one of the country’s leading trainers.

Horses have been part of his life since a very young age. Growing up in the family’s ancestral seat of Manderston, in Berwickshire (Scottish Borders), he was exposed to horses early on. He says half-seriously, “I spent too much time at the betting shop.” But, “I love the horses, I love dealing with them. It’s a lovely lifestyle. It’s just the one I understand the most.” That passion soon became a profession when he started training under famed trainer Gai Waterhouse in Australia.

It was Palmer who told me that bit about Charles II following Nell Gwynn to Newmarket and inadvertently creating the start of what would be a billion-pound industry in the UK today.

To watch Palmer is to watch a consummate professional at work. In between showing us Kremlin Cottage Stables and taking us up to Warren Hill and the Downs to check on how his horses were training, he talks about the profession he’s in. “While we’re talking, I have deadlines coming up. I’ve got to choose which horses to enter this weekend. By 10 o’clock I have to work out where exactly they’re going to run.” It’s a lot of responsibility, particularly since these are Thoroughbreds worth millions of guineas. Given how expensive these animals are, I wonder about what owners expect.

“The job of a trainer is to manage expectations,” he reflects, adding, “Many of the owners send their horses to me because they consider that I may give their horses a good chance of winning… Unfortunately, majority of the horses are like people, they’re slow. The champions are quite few and far between.” Few they may be, but in his short career, he’s trained some winners. For instance, he won his first Classic in 2015 at the Irish Oaks with filly Covert Love, who would repeat the feat that same year in the Group 1 Prix de l’Opera on Arc weekend in Paris. The following year, he won his first Classic race in the UK, the 2000 Guineas, with Galileo Gold, owned by Al Shaqab, the racing operation for Sheikh Joaan Al Thani of Qatar. The 2000 Guineas is the first Classic in the British calendar and is staged at Newmarket’s Rowley Mile racecourse.

Galileo Gold also triumphed in the St James’s Palace Stakes at Royal Ascot against a highly competitive field later that summer. Palmer has also enjoyed back to back wins in the 1000 Guineas in Germany, winning the Classic contest with Hawksmoor (2016) and Unforgetable Filly (2017).

It’s a safe bet then that he can pick winners – or at least, know what to look for in a Thoroughbred. “One is a fluent athletic range of movement” – an innate grace, if you will; the other is physical. “Good sloping shoulder, heart and lung capacity, without which no athlete, equine or human can perform.”

Stars of the show

It’s probably a safe bet too that Palmer, along with most trainers and owners the world over, go to Tattersalls for their horseflesh. Tattersalls offers 10,000 Thoroughbred horses each year at 15 sales at either its Newmarket headquarters in England, or at Fairyhouse outside Dublin, in Ireland. At Tattersalls auctions in Newmarket, the horses are still priced in guineas, a coin that was minted in England between 1663 and 1813 and is no longer in use. Its original value was 21 shillings (now the equivalent of one pound and five pence).

I didn’t manage to get into an auction, which is held at different times of the year, but just to walk around the storied stables is fascinating.

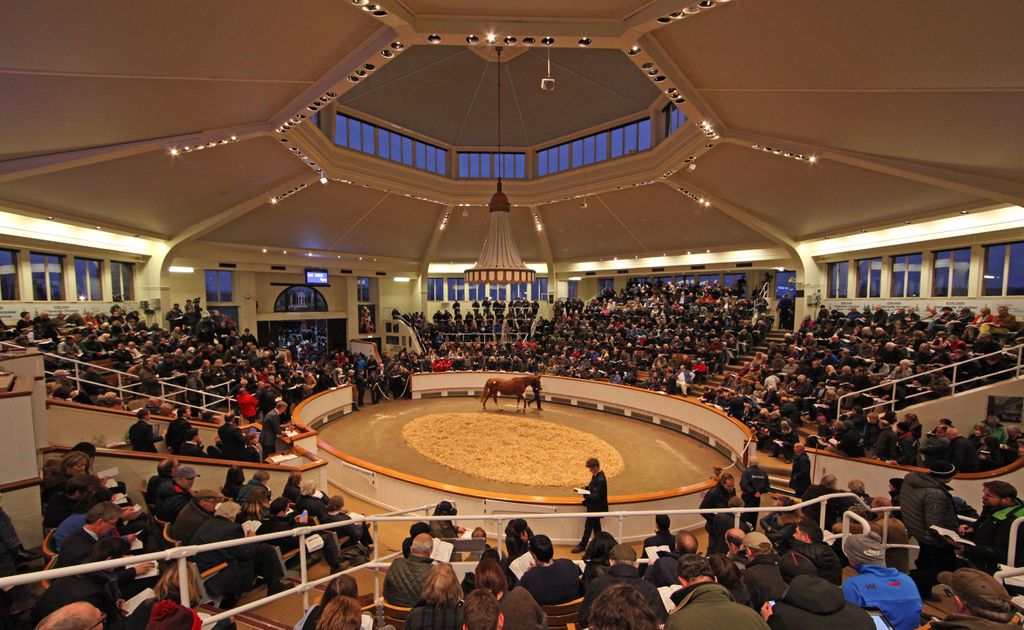

The sales ring is an impressive sight, evoking both the big ring in a circus and strangely enough, a courthouse, with its rows of gallery seating, the better to see the horses. Horses about to be auctioned enter one set of doors and are paraded around the centre ring before exciting in another set of doors. Here, oil barons, sheikhs, trainers, and spectators sit side by side to watch as one by one, horses enter the building as bidding starts. The horses are the stars here, and why not? When millions are potentially at stake in one race, the search for a likely winner can become a high-stakes game.

As Palmer says, “The hope is that these horses win,” and it is that hope that buyers come to Tattersalls to bid against each other for foals, yearlings, mares and horses in training. It is essentially hope that they’re buying, if one gets down to it. After all, expensive as these Thoroughbreds may be, the true test lies in the racecourse, where their mettle is tested. If they fail to win, then the owners don’t recoup their investment.

Which is why each horse is inspected thoroughly and its pedigree scrutinised. “Genetics are important,” says Palmer. “But you have to bear in mind that every horse that is a stallion has a high level of ability, otherwise he won’t be a stallion. The dud, the horse that can’t get out of its own way, doesn’t reproduce. A lot of it comes down to the female side. A good female family is almost more important than the stallion. Ideally you’d have to have both.” Which is why owners and agents pay good money for horses that come from winning stock.

This is also why they all come to Tattersalls to buy their stock. The firm has maintained its reputation for the quality of the horses they sell, after more than 250 years since founder Richard Tattersall began selling horses in Hyde Park Corner in London. It was only in 1965 that Tattersalls moved to Newmarket to occupy Park Paddocks, with its sale ring, hundreds of stables and elegant offices.

For many who attend the sales, whether part of the racing community or as a spectator, Tattersalls is an experience. The manicured grounds feel like you’re in a country house, with its iconic cupola in the middle, containing the bust of George IV and the fox at the centre, one paw raised, which is the firm’s symbol. That bucolic gentility belies the heady feeling of competition that pervades the air during a Tattersalls sale. After all, when it comes to the sport of kings, the race starts with the successful bid of the perfect horse.